Journal of Oil Palm Research Vol. 33 (1) March 2021, p. 171-180

A REVIEW ON MALAYSIAN SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL CERTIFICATION PROCESS AMONG INDEPENDENT OIL PALM SMALLHOLDERS

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21894/jopr.2020.0056

Received: 25 July 2019 Accepted: 30 January 2020 Published Online: 10 September 2020

In recent years, palm oil faces various issues on the global market. Therefore, Malaysia launched Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification as the national scheme to systematically certify palm oil industry in Malaysia as an effort towards sustainable production as well to address some of the issues raised on the global market such as the requirement by importing countries for a completely certified sustainable palm oil supply chain. Various strategies have been developed to effectively certify independent smallholders such as the establishment of Sustainable Palm Oil Clusters (SPOC). The aim of this article is to extend knowledge and experience gained towards MSPO certification approach among independent oil palm smallholders in Malaysia. It also provides a basis for operation frameworks towards certification approach for smallholders especially in developing countries. Apart from that, this article highlights the progress and national initiatives on the establishment of MSPO certification in Malaysia. It gives insight on the challenges and way forward of MSPO certification approach in Malaysia.

KEYWORDS:Palm oil has been one of the major sources of oils and fats in the world (Kushairi et al., 2018). Oil palm crop is known to be highly productive compared to other competing crops due to its high yield per hectare as well as the low requirement of land area (Rival and Levang, 2014; Morley, 2015). Palm oil is well-known for its versatility which have been used in various sectors including non-food sector and well-known as a renewable energy feedstock other than its major role in providing food security to the world. Despite being the most efficient oil crop, palm oil has been suffering from various anti-palm oil sentiments and increasing scrutiny over the years (Murphy, 2014). Some of the issues on the global market are on the allegations and misunderstandings about oil palm industry which are linked to intensive deforestation and destruction of biodiversity. There is a concern on the trend of increasing food standards which might act as a new trade barrier for developing countries (Augier et al., 2005; Brenton and Manchin, 2002; Ferrantino, 2006; Garcia and Poole, 2004). Increasing complexity of standards imposed on small farmers by global market creates some advantages as well as disadvantages among small farmers especially for export market (Humphrey, 2006). The palm oil industry faces various issues especially in Europe which started in 2015 with the Amsterdam Declaration which calls for a complete sustainable palm oil supply chain in Europe by 2020. Following that, the European Parliament Environmental (ENVI) report stated few recommendations on palm oil and deforestation with one of them is to eliminate the use of vegetable oils that cause deforestation as a component of biofuels in which it included palm oil. Then ENVI voted to ban palm oil biofuels from Europe from 2021, as part of the European Union (EU)’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED). Malaysia takes continuous effort to improve and elevate the palm oil industry to the global standard by addressing various requirement imposed by stakeholders as well as to cater for the growing global demands for vegetable oils. In 2018, the largest Malaysian palm oil exports markets were India with a total of 2.51 million tonnes followed by EU with a total of 1.91 million tonnes (Kushairi et al., 2019). Markets for certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) in developed countries especially the EU have been on the increasing trends. In near future, these trends are expected to influence other traditional markets such as China, India and Pakistan to demand for CSPO. Oil palm which was initially brought in as an ornamental plant has become a major industry for Malaysia. After more than a century of commercial cultivation of oil palm, Malaysia currently has 5.85 million hectares of oil palm area (MPOB, 2018). Palm oil production is vital for the socio- economic development of Malaysia especially the independent oil palm smallholders which account for 16.8% of the total planted area in Malaysia. Palm oil in Indonesia has been a powerful tool for poverty alleviation especially for smallholders by creating job opportunities and creates spin-off economic activities (Edwards, 2015).

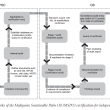

Desk research was conducted to review certification approach for smallholders in Malaysia. Primary data on readiness assessment among smallholders prior to joining the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification were gathered through survey questionnaire using an information and communications technology (ICT) tool. Apart from that, data on cost of certification as well as the frameworks on the MSPO certification and other relevant data were gathered from internal sources available at the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB).

MSPO Certification

Although the word sustainability can be traced back much earlier in history, it becomes widely used after the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) which describes it as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Three fundamentals of sustainable development were highlighted which consist of environmental protection, social responsibility and economic practices. Since then, various certification standards have been developed all over the world using sustainability as their fundamentals (DeFries et al., 2017; Potts et al., 2014).

In Malaysia, there are several palm oil certification standards currently being used. However, the most common standards are MSPO, Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), and International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC). RSPO is an international oil palm certification scheme developed in 2004 which consists of members from all stages of oil palm supply chain. ISCC was introduced in 2010 mainly for certification of palm oil used as a feedstock for biofuels. Other than that, Indonesia has introduced their own certification scheme known as the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) in 2011 to certify palm oil industry in Indonesia.

The report on United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (1992) on Agenda 21 consists of a comprehensive plan of action, recommended by UN summit to be taken globally. In Agenda 21, article 8.6 states that, countries could develop systems for monitoring and evaluation of progress towards achieving sustainable development by adopting indicators that measure changes across economic, social and environmental dimensions. Standards developed in different parts of country or geographical area might not be effective to other countries if the standard does not cater for local conditions. Local requirement and crop specific standards can be further incorporated into a generic standard to make sure the criteria are not superfluous (Dankers and Liu, 2003). Therefore, in 2013, MSPO certification scheme was launched as the national scheme for Malaysia to systematically certify palm oil industry in Malaysia. Since then, MSPO implementation has been on a voluntary basis until the government announced its mandatory implementation in 2017. Initially, the mandatory timeline for companies that have been certified under RSPO need to obtain MSPO certification by 31 December 2018 while companies without RSPO certification were given extended time until 30 June 2019. Independent and organised smallholders were given until 31 December 2019 to obtain MSPO. However, recently the timeline were revised to a single timeline where the implementation of MSPO certification for all categories would be made mandatory by 31 December 2019. In 2014, an independent non-profit organisation known as the Malaysian Palm Oil Certification Council (MPOCC) was established as the scheme owner to implement and operate the MSPO certification scheme in Malaysia.

Initially, MSPO was initiated by MPOB in 2010 where MPOB is the authorised Standards-Writing Organisation (SWO) appointed by SIRIM Bhd which is the national standards development agency to develop the standards. Prior to MSPO, MPOB has been implementing the MPOB Codes of Practice (CoP) since 2007 to assist the industry on the best practices throughout the palm oil supply chain. The MSPO standards was developed by MPOB through a standards development process under the purview of the Department of Standard Malaysia (DSM) which is the National Standards Body and the National Accreditation Body with inputs from relevant stakeholders of the oil palm industry. MSPO scheme contains four parts such as MSPO 2530-1:2013 Part 1: General principles, MSPO 2530- 2:2013 Part 2: General principles for independent smallholders, MSPO 2530-3:2013 Part 3: General principles for oil palm plantations and organised smallholders, and MSPO 2530-4:2013 Part four: General principles for palm oil mills. In addition, MSPO Supply Chain Certification Standard (SCCS) was launched by MPOCC to extend the standard to the downstream industry. MSPO is seen as the Malaysia’s answer to the Amsterdam Declaration which wants a complete certified sustainable palm oil supply chain in Europe by 2020 with the hope that MSPO is accepted as a certification system in Europe. The Amsterdam Declaration is currently signed by European countries of Denmark, Germany, Norway, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France and Italy to show their commitment to support a fully sustainable palm oil supply chain by 2020.

According to the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), certification means the provision by an independent body of written assurance (a certificate) that the product, service or system in question meets specific requirements. To achieve this, the auditing and certification process are carried out by independent certification bodies (CB) which are subject to accreditation by DSM in accordance to the international standard of MS ISO/IEC 17011 (Ainie et al., 2015). Currently, there are 13 CB consisting of both international and local companies involved in certifying independent smallholders in Malaysia. Application of MSPO part 2 for independent smallholders are currently under the purview of MPOB. Meanwhile, application of MSPO part 3 for oil palm plantations and organised smallholders and MSPO part 4 for palm oil mills are currently under the responsibility of MPOCC.

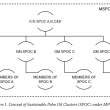

Concept of Sustainable Palm Oil Clusters (SPOC)

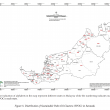

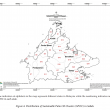

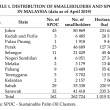

As of April 2019, there are 262 724 independent smallholders owning 1 015 524 ha of oil palm in Malaysia. Independent smallholding are defined as those who own oil palm land less than 40.46 ha or in aggregate amount of less than 40.46 ha. These smallholders are scattered all over the country with various age profile and practices while managing their oil palm land on their own. The average land

Agro Eco and Grolink (2008). Organic Exports, A Way to a Better Life? Export Promotion of Organic Products from Africa. Report publication. http://www.grolink. se, accessed on 30 March 2019. 105 pp.

Ainie, K; Kushairi, A and Choo, Y M (2015). Malaysian sustainable palm oil. Oil Palm Bulletin No. 71: 1-7.

Amekawa, Y (2013). Can a public GAP approach ensure safety and fairness? A comparative study of Q-GAP in Thailand. The J. Peasant Studies, 40(1): 189- 217.

Augier, P; Gasiorek, M and Lai, T C (2005). The impact of rules of origin on trade flows. Economic Policy, 20(43): 567-623.

Ayat, K A R; Ramli, A; Faizah, S and Arif, S (2008). The Malaysian palm oil supply chain: The role of the independent smallholders. Oil Palm Industry Economic J. Vol. 8(2): 17-27.

Basiron, Y and Foong, K Y (2016). The burden of RSPO certification cost on Malaysian palm oil industry and national economy. J. Oil Palm, Environment and Health, 7: 19-27.

Brandi, C; Cabani, T; Hosang, C; Schirmbeck, S; Westermann, L and Wiese, H (2015). Sustainability standards for palm oil: Challenges for smallholder certification under the RSPO. J. Environment and Development, 24: 292-314.

Brenton, P and Manchin, M (2002). Making the EU Trade Agreements Work: The Role of Rules of Origin. Working Document 183. Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels. 26 pp.

Byerlee, D and Rueda, X (2015). From public to private standards for tropical commodities: A century of global discourse on land governance on the forest frontier. Forests, 6(4): 1301-1324.

Dankers, C and Liu, P (2003). Environmental and Social Standards, Certification and Labelling for Cash Crops. FAO Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper No. 2. Food and Agriculture Org, Rome. 111 pp.

Defries, R S; Fanzo, J; Mondal, P; Remans, R and Wood, S A (2017). Is voluntary certification of tropical agricultural commodities achieving sustainability goals for small-scale producers? A review of the evidence. Environmental Research Letters, 12(3): 033001.

Edwards, R (2015). Is Plantation Agriculture Good for the Poor? Evidence from Indonesia’s Palm Oil Expansion. Working Paper No. 2015/12. Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University. 61 pp.

Ferrantino, M (2006). Quantifying the Trade and Economic Effects of Non-tariff Measures. OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 28. OECD Publishing, Paris, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/837654407568 70 pp.

Fontaine, D; Gaspart, F and De Frahan, B H (2008). Modelling the impact of private quality standards on the fresh fruit and vegetable supply chains in developing countries. Paper presented at the 12th EAAE Congress – People, Food and Environments: Global Trends and European Strategies. Gent, Belgium. 26-29 August 2008.

Garcia, M and Poole, N (2004). The development of private fresh produce safety standards: Implications for developing Mediterranean exporting countries. Food Policy, 29(3): 229-255.

Humphrey, J (2006). Policy implications of trends in agribusiness value chains. The European J. Development Research, 18(4): 572-592.

Kushairi, A; Meilina, O A; Balu, N; Elina, H; Mohd Nor Izuddin, Z B; Razmah, G; Shamala, S and Ghulam, K A P (2019). Oil palm economic performance in Malaysia and R&D progress in 2018. J. Oil Palm Res. Vol. 31(2): 165-194.

Kushairi, A; Soh, K L; Azman, I; Elina, H; Meilina, O A; Zanal, B M N I; Razmah, G; Shamala, S and Parveez, G K A (2018). Oil palm economic performance in Malaysia and R&D progress in 2017. J. Oil Palm Res. Vol. 30(2): 163-195.

Laila, K; Subasingae, R and Philips, M (2011). Aquaculture Farmer Organizations and Cluster Management: Concepts and Experiences, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 563. FAO, Rome. 104 pp.

Morley, D (2015). RSPO, the global standard for sustainable palm oil. Agro Food Industry Hi-tech, 26(6): 29-30.

Murphy, D J (2014). The future of oil palm as a major global crop: Opportunities and challenges. J. Oil Palm Res. Vol. 26(1): 1-24.

Malaysian Palm Oil Board (2018). Overview of the Malaysian oil palm industry 2018. http://bepi. mpob.gov.my/images/overview/Overview_of_ Industry_2018.pdf, accessed on 1 December 2019.

Nia, K H; Pieter, G and Astrid, O (2015). Sustainability certification and palm oil smallholders’ livelihood: A comparison between scheme smallholders and independent smallholders in Indonesia. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 18(3): 25-48.

Parthiban, K; Nurhana, B; Khairuman, H; Hamdan, A B; Wahid, O; Shahrun, N K; Zamri, M S and Nurhanani, M (2017a). Monitoring and reporting of oil palm fresh fruit bunch (FFB) transactions among independent smallholders and dealers: An analysis of a case study in Selangor, Malaysia. Oil Palm Industry Economic J. Vol. 17(2): 68-81.

Parthiban, K; Tan, S P; Siti, M A; Idris, A S; Ayatollah, K; Khairuman, H; Hamdan, A B and Wahid, O (2017b). Knowledge assessment of basal stem rot disease of oil palm and its control practices among recipients of replanting assistance scheme in Malaysia. International J. Agricultural Research, 12(2): 73-81.

Phillips, M; Subasinghe, R; Clausen, J; Yamamoto, K; Mohan, C V; Padiyar, A and Funge-Smith, S (2008). Aquaculture production, certification and trade: Challenges and opportunities for the small- scale farmer in Asia. Aquaculture Asia Magazine, 13(1): 5-8.

Potts, J; Lynch, M; Wilkings, A; Huppe, G; Cunningham, M and Voora, V (2014). The State of Sustainability Initiatives Review 2014: Standards and the Green Economy. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Manitoba, Canada and London, United Kingdom. 354 pp.

Rival, A and Levang, P (2014). Palms of Controversies: Oil Palm and Development Challenges. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor, Indonesia. 59 pp.

* Malaysian Palm Oil Board,

6 Persiaran Institusi,

Bandar Baru Bangi,

43000 Kajang,

Selangor, Malaysia.

E-mail: parthiban@mpob.gov.my

** Solidaridad Network Asia L-2l-01,

Connection Commercial Persiaran IRC 3,

IOI Resort City,